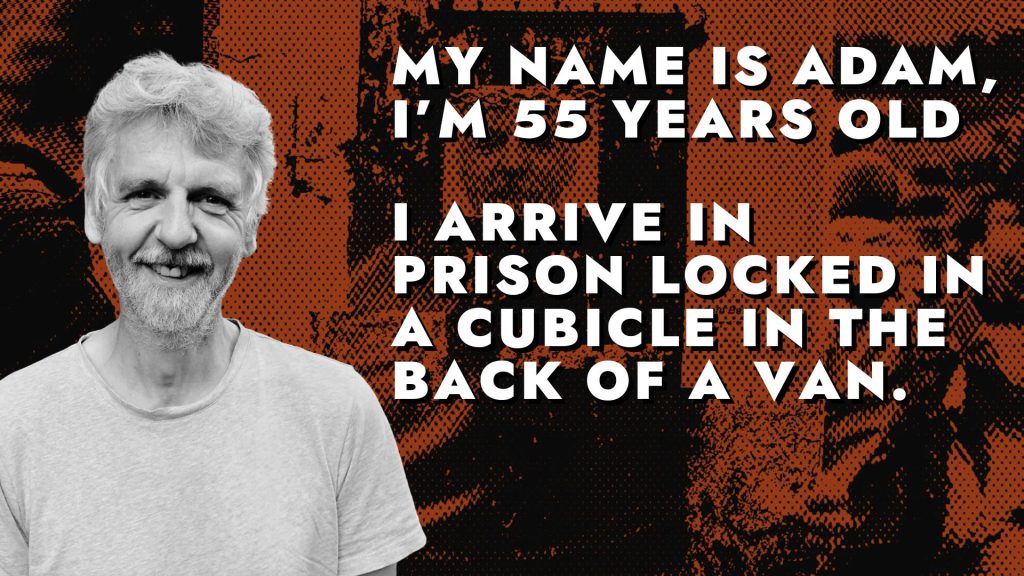

I arrive in prison locked in a cubicle in the back of a van. Through the small window I see a sign: ‘Welcome To HMP Wandsworth’. If it’s meant to be reassuring it doesn’t work for me.

I am taken into a dirty, airless room. It fills up with about twenty men. Some look afraid while others put on displays of macho bravado. A few rant about the unjust circumstances that led them here. Reminding myself that I expected to be here today, I stay close to the small group I was arrested with. We exchange encouraging glances and wait.

One by one our names are called. When my turn comes, I follow the guard to a desk where a sour-faced officer jabs questions at me, like accusations.

‘Name?’

‘Use drugs?

‘Gang issues?’

She’s clearly not looking for conversation so I give one-word answers. After another wait I see a nurse. She’s much friendlier but pushed for time so the conversation here too is brief. Once she’s satisfied I’m not a suicide risk, I’m sent to wait again before being taken to the wing and led into a cell. The heavy steel door bangs shut behind me. There is no handle on the inside.

So began my seven month stay in prison, a new experience both scary and disorientating; a harsh world of noise, unfamiliar routine and rules that new inmates are left to work out as best they can.

When I decided to take direct action at Heathrow airport in support of Just Stop Oil’s campaign for a fossil fuel free future, I knew there was a high chance of being remanded: being sent to prison before a trial takes place. Just Stop Oil’s actions follow the principles of non-violence as practised by Gandhi and developed by Martin Luther King. Non-violence differs from not being violent in that it is an active state; seeing harm being done demands a response to try to prevent it. The climate crisis, inflicted on us by grasping fossil fuel executives and the corrupt politicians they control, is not only causing harm to millions of people around the world, but threatens the lives of countless generations to come. I feel a moral duty to act. Another facet of non-violence is accountability. When we take action we wait for the police and do not resist arrest. Thus, unlike almost all my fellow inmates, I effectively chose to go behind bars.

There are over 88,000 people in British prisons, 95% of whom are men. This is the highest rate of incarceration in Western Europe. Of all the people I met inside, only a few had been involved in pre-meditated violent crime. Many were there following a momentary loss of control, or had been in situations they were not equipped to deal with. Many had unstable and traumatic backgrounds.

For four months I was locked in my cell for 23 hours a day. As the Roman slave Epictetus taught, we can’t always control our circumstances, but we can control how we respond to them. I found that a very helpful way to approach the loss of agency that prison entails.

A typical day began around 09.00 when my cell door was opened, marking the beginning of an hour of relative freedom. This was my opportunity to go to the yard for some precious time outdoors, but sadly also the only time to try to shower and do admin such as filling out forms for visits or queuing in the hope of some clean sheets being available.

I prioritised time in the yard, a tarmacked area infested with rats and covered with netting to prevent contraband being delivered by drones, but still precious as my only chance to be outdoors. A chance to see the sky, feel the weather and move more than the three metres available in my cell.

Prisons by nature are violent places. Many inmates suffer from pent-up anger so fights do break out, but I was struck by how people generally tried to make the best of the challenging situation and support each other. Some people I realised were best avoided but there were others I could chat and share a joke with.

Spending so many hours locked in my cell was a challenge; I was determined to use the time as best I could. I read many books and wrote letters. A particular pleasure and distraction was learning about creative writing from a book sent in by a friend.

Each day we were given a food bag containing a bread roll, a piece of fruit, cereal and tea-bags. And a small carton of UHT milk I was happy to give to a neighbour. One day I asked if he had any spare fruit. He didn’t, but later gave me some apples. He didn’t say so, but I worked out another prisoner owed him, and he had decided to call in his debt to be able to give me something in return. It was little acts of kindness like these that made life in such a hostile environment bearable.

Alongside my fellow inmates, I quickly learnt which guards to avoid and which to ask when I needed something. Like so many public servants, many wanted to help people but found themselves constrained by a system crumbling thanks to years of cuts, understaffing and overcrowding. On hearing why I was in prison, many guards expressed outrage that the state is locking up peaceful protestors.

After months of trying I was given work teaching other prisoners to read, something many of them struggled with. One of my students, Abdul, a young man from Eritrea and brought up in London, had missed out on schooling but was keen to learn, not least so he had something to do with all those hours in his cell. He also recognised that reading would open up a whole world of learning to him.

Wanting to be seen to be ‘tough on crime’, successive governments have increased the length of prison sentences. While research has shown that the criminal-justice system acts as a deterrent, the actual length of sentences does not. This is borne out by the continued high rate of re-offending which demonstrates how little rehabilitation takes place in our prisons. Michael is in his sixties and has been in and out of prison for most of his life. Behind an impressive array of facial scars and a tough ‘don’t-fuck-with-me’ demeanour, beat a kind heart. He was another of my students and we started right at the beginning, learning the sounds of each letter. Though hampered by ADHD he persevered and after a few weeks was able to read me short sentences. He was reluctant to show it but I could tell he was proud of his achievement. I hope that in a small way I have given him something to help him stay out of prison after the end of his current sentence.

Many inmates described their time in prison as wasted. While I can’t say it was a good place to be, I got to know people I would not otherwise meet and see another side of life. I witnessed shocking displays of racism and misogyny, but also saw at first hand genuine humanity.

As I write I await sentencing and am likely to be given more time in prison. Whilst I do not want to go back I have absolutely no regrets about taking the action I did. This is no time to be a bystander – I will know that I have done all I can to stop the burning and extraction of gas and oil by 2030.

Names have been changed to protect identities.

Adam Beard was found guilty of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance at Isleworth Crown Court, he is currently bailed and will appear in court to be sentenced on May 16th.